Over the past few years, I have collaborated on several initiatives that implement insights about embodied social cognition in the everyday working routines of researchers. Throughout this time, I was in continuous exchange with researchers interested in holistic, participatory and process-oriented work. This has strengthened my interest in questions of flourishing and sustainable development:

- What characterises situations in which all parties are involved on their own accord, get to relate, participate and take their time off, alas live and leave (die) well?

- Which skills are required to collaborate based on values and principles, instead of fixed hierarchies, norms and rules?

- How can inner and outer development be integrated? That is, which physical and social infrastructures support emotional intelligence and our capacity to relate, reflect and express?

- How can our traditions integrate diverse forms of life (individual, group and organisation – plant, animal and inanimate alike)?

In the following, I outline a response to these questions – my Vision for Education on Inner Development towards Sustainable Action in the World.

What will I be talking about? My view on sustainable development encompasses “that which happens when we are attuned to the choir of activity that constitutes our environment”: our self (body, social identity), important others, natural environment (bioregion, seasons, climate) as well as traditional forms of organisation and institution that (pre-)structure our everyday life. Given this focus on relations, I suggest that a combination of being well alone (trusting one’s judgement and acting upon it) and being well together (knowing how to share joy and laughter, as well as commitment and hardship) is key to sustainable development. I hence place the ability to relate well at the heart and foundation of sustainability.

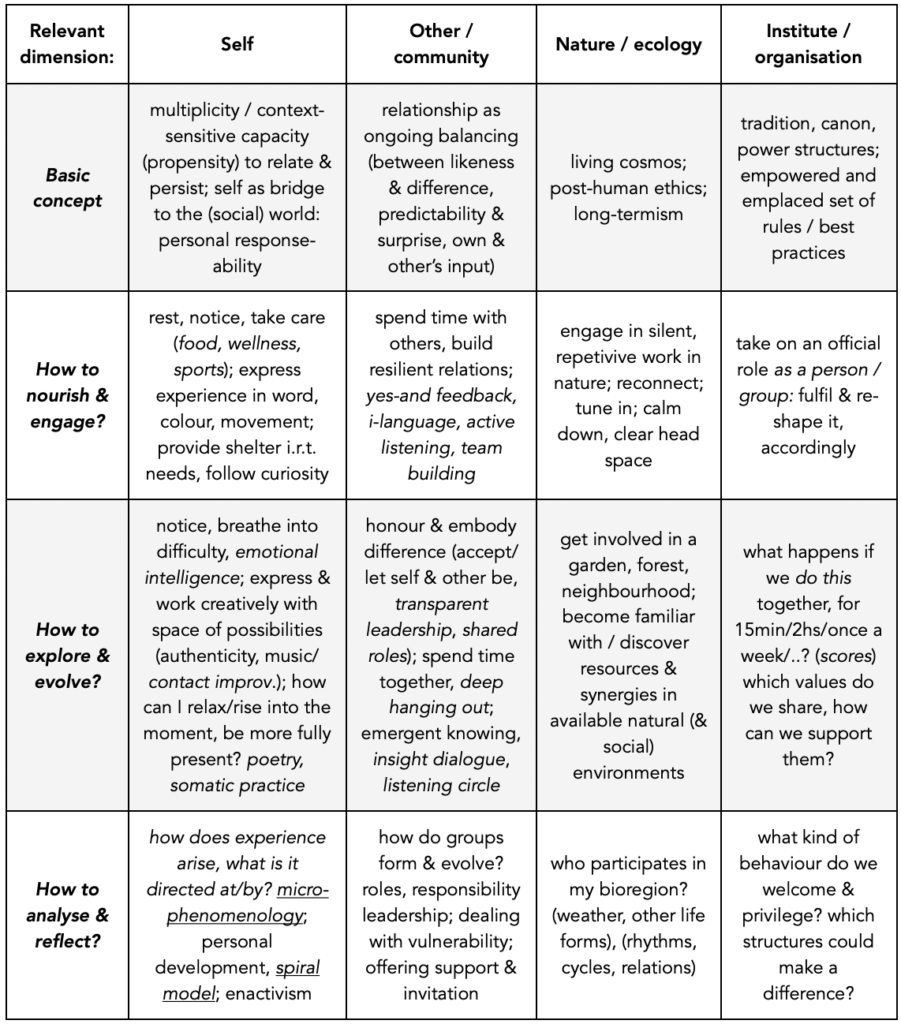

Below, I introduce thoughts on each of these five topics. After that, I say a few words about my background, and offer an overview of basic concepts, useful tools and research questions (see Table 1).

Relationship

I posit that life is participatory, across scales of observation (see also Varela et al, 1991; De Jaegher & Di Paolo, 2007). If we accept this as true, then learning and development of living beings are bound by relational skills (the ability to navigate relations) and the presence of meaningful (deep, long-lasting) connections to the world (see also Candiotto, 2022). Relations thrive on authentic sharing, curiosity and space for the other, as well as real commitment – being effective together in the world. Relating means listening, taking care of what matters and inviting others into active participation – with outcomes that depend on everybody’s heartfelt engagement. True relationship implies continuous renewal, reflection as well as integration – what we do reflects who we are (becoming). The shift I propose towards more sustainable development hence calls for a more dynamic concept of orientation and security, with other kinds of (un)certainty, vulnerability and personal risk/freedom involved.

Self

I picture selves as importantly physical and social, multiple and dynamic in both domains. The needs, interests and outlook we experience as a person vary – according to the (lack of) food and bacteria in our system, the strength and flexibility of our body, the emotions and roles we have grown into, the presence or absence of supportive and inspiring others – in short: the resources we have available to be and participate well.

Selves are at ease, breathe spaciously, perceive clearly and joyfully, move with strength and flexibility, when they learn about their needs, interests and difficulties: when they can notice, express and take care of what matters, so that a rich pool of resource forms around the things they truly value. Being a full self means building a life that continues to nourish and deepen our sense of connection – with the important others that meaningfully surround us.

Based on this perspective, education amounts to dialogue with and as whole selves. To include the body and affective life in professional environments; to provide time and space for personal reflection and recreation; to develop curiosity and care for the others that grow next to our paths; to offer tools that may deepen our relationship to the phenomena and principles we care about; to encourage voice and creative resource by offering our company (experience, support, compassion) as others hone their skills and forge a path of their own.

Others

If life is relationship, others are central: we are who we are (can be) with important others in our lives. The relationships between students, teachers and the academy as a whole, including its infrastructure and surroundings, become a central organ of education. From this viewpoint, classes and learning environments should involve work in dyads and small groups, encourage students to meet and organise among themselves, as well as to contribute to the development of the study group (and academy) as a whole. Besides offering diverse formats for exchange and practice, classes should focus on leadership and team development, for example through shared roles (co-facilitation), dialogue settings that welcome differences and prepare us to engage with uncomfortable feelings and conflict. Common to all these ingredients is a belief in the value inherent to (respectful) difference and distance: beyond the similarities that attract and bind us to others, differences are exciting and enable us to learn and grow – they accompany us throughout our lives.

Environment

Just as our body and close relations, the environments we frequent make up the fabric of our life. I envision future-oriented learning environments to bring students (and teachers) into dialogue with the (eco)systems and (bio)regional organisation that sustains life in this particular university and place on earth. What is taught at the university should come about in dialogue with the diverse traditions of practice that surround and sustain us: hubs of local activity on and off campus. Teaching then means inspiring personal, ecological and sociocultural relevance (conversation). Exchange and activity (development) beyond any given text book, library or university. Relatedly, courses as well as research projects are open to anybody (e.g. members from the working population, family, wildlife), providing outlets for the education that is offered, as well as diverse (real) links to living contexts. Biotopes on and around the campus – (wild) forests and gardens – could serve as hubs for ecological learning: spaces in which diverse others are welcome to leave their traces (human and non-human alike), get to know each other’s circadian and seasonal cycles and form inspiring short and long-term relationships (see also Addey, 2016).

By building bridges to the (bio)region, higher education provides students with opportunities to discover synergies between their different professional and personal backgrounds and the (local) natural environment, and encourages them to reflect on the environmental implications of the profession they chose. The university is then a platform for the development of ecological relationships – alliances with the diverse others who care about this place (or professional practice) as the basis for their life making.

Organisation

I imagine an academy that models respectful participation at eye’s level: buildings, administrative or governmental structures, approaches to collaboration and teaching that involve visitors, participants and representatives in ongoing and co-creative development of the tradition they serve.

Acknowledging the importance of healthy relationship, these structures attend equally to physical, emotional and mental needs and resources, and connect with the weather and other (bio)regional activity as tangible phenomena.

Understanding itself as the primary vessel for research and development, the organisation of the university employs research as a means to share and evolve its best practices: is our everyday practice aligned with our values and mission? Whom does our work depend on or affect – do they get to speak to and benefit from how we run the place?

In this way, universities would birth professional identities that bring bioregional sensitivity to global challenges. In other words, educated thinkers, future leaders who identify and act as part of a large and diverse ensemble.

Annika Lübbert. I am a cognitive scientist with a focus on integrating quantitative and qualitative perspectives on social interaction. As part of my PhD, I joined a European FET Horizon 2020 project and taught basic physiology to medical students. Following my interests and line of work, I formed strong links within and outside my research consortium. In particular, I frequently visited the Interacting Minds Center in Aarhus, Denmark, leading to shared publications and ongoing collaborations to publish my empirical work. I also became an active member of Mind and Life Europe: most recently, I contributed as co-chair, presenter and facilitator to their 2022 Summer Research Institute, a yearly conference dedicated to fostering dialogue between contemplative practice and scientific research.

Besides my empirical work, I co-developed several initiatives to apply my theoretical background directly to the way I work as a researcher.In particular, I co-authored the Playful Academic, which provides a general introduction and set of protocols that prepare researchers to bring embodied and interactive creativity into their work. The Mindful Researchers, in turn, was an online practice group for international researchers: in weekly smaller group meetings and series of community events, we introduced and experimented with embodied awareness and co-creative exchange at eye’s level as central elements of doing scientific work.

As a trainee with hfp consulting, I form part of a global network of academics dedicated to inner development and humanistic values. Through my experience with movement practices (diverse sports, bike-packing, contact improvisation), and a bioregional approach (gardening, crafts), I come with strong footing in ‘being local’. I consider both important complements to my academic background, when I imagine my professional contribution to a more lively and deeply rooted society of the future.

Table 1. Overview of key dimensions of sustainable development and ways to nourish and develop them further. Note that methods and research questions may be relevant beyond a particular row or column of this table.